Community Health Partnership’s (CHP’s) mission is to transform the way people work together to solve complex community health issues. The issues CHP engages in are not only complex, they are also chaotic. There are no simple solutions and decisions are never obvious.

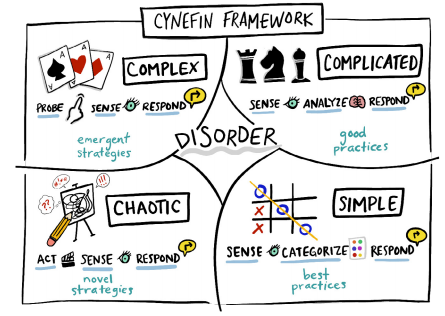

The process for addressing a “simple” problem (e.g., baking a cake) is to make sense of the issue, categorize the next steps, and then respond appropriately. The process for a chaotic issue (e.g., raising a child) is to act, engage in a sense-making process, and then respond. Compared to best practice, working in complexity and chaos requires emergent and novel strategies.

As leaders (like parents), we don’t intuitively know how to engage in complexity. Learning how to effectively engage to address “wicked” problems requires a new set of skills and leadership capacities. This type of leadership includes a willingness to confront long-standing, systemic problems with vulnerability, authenticity, humility, and genuine community engagement. This is why one of CHP’s three core beliefs is that we need a different type of leadership – one that builds the muscles needed to thrive in chaos versus getting paralyzed by it.

Shaking up traditional leadership approaches and power structures isn’t easy. Our society has deeply ingrained ideas about what effective leadership looks like. Few people are willing to give up what they are comfortable with in order to try something completely new and untested, or emergent and novel.

That’s why, over the last three years, CHP has been experimenting, adapting, and putting this belief into practice, starting with our staff and board.

From Challenge to Catalyst

CHP has been on quite a journey since its inception in 1992. Originally founded by several local healthcare organizations to collaboratively address gaps in the system, CHP took on the Regional Care Collaborative Contract (RCCO) in 2011, providing direct service to Medicaid members and providers in El Paso, Teller, Park, and Elbert Counties. When CHP lost the contract in 2018, it faced an uncertain future.

This challenge turned into an opportunity. Amber Ptak, who became CHP’s CEO in 2019, says that, “It was an opportunity for CHP to redefine itself as a community catalyst, a gateway to transformative change, and a resource to bring fresh perspectives to the table. Unfortunately, the transition from the RCCO to transforming the way people work together to solve complex community health issues was anything but easy. We, too, had to learn a new way of working with our staff and board so that we could model the foundational practices we are building in community. We had to reflect deeply on this new type of leadership we hope to build and/or support, while articulating what is needed to engage in this exceedingly challenging work.”

Although the idea of a new type of leadership wasn’t yet fully formed, Amber intuitively and intentionally moved the board and staff in that direction. Over time, the organization identified three key foundational practices that are the bedrock to leading and working in a different way: relational capacity, reflective capacity, and strategic learning.

Relational Capacity

CHP defines relational capacity as the ability to build and maintain quality relationships that have a foundation of trust and accountability. Board Chair Patricia Yeager, who has been a member of the board for five years, has had a front row seat to the evolution of CHP and its board of directors under Amber’s leadership. Patricia credits Amber’s focus on relationship-building for creating an atmosphere of trust and authenticity among board members.

Forming strong bonds within a group is necessary to work together effectively. It takes time but it doesn’t have to be a chore. At every board retreat, for example, the group engages in something fun and low stakes, like cooking a meal together or building a terrarium. These moments strengthen their relationships in a way that opens the door for deeper, more meaningful work.

“It’s hard to work with someone collaboratively if you don’t know them and don’t trust them,” says Patricia. “If you have to have a difficult conversation with someone, it’s a lot easier to do if you have a relationship with them. Having a relationship means having empathy for that person’s position. Empathy is a necessary component to building the practice of relational capacity.”

Amber notes that relational capacity also requires vulnerability, curiosity, and humility. “These traits are so important to connect across differences and to understand and address issues of power and equity in the work.”

Reflective Capacity

Systems change requires leaders to develop and lead from a place of greater self-awareness and organizational awareness. Engaging in reflective capacity means slowing down, questioning assumptions, and examining one’s own mental models. “Having the ability to pause, reflect, and learn from experiences helps leaders make better decisions, be more innovative, and drive meaningful change,” says Amber.

Recently, the board had the opportunity to practice this skill in real time. Three community members were invited to a board meeting as part of a panel to share their honest, firsthand experiences with the mental health system in Colorado Springs. Amber says she wasn’t sure how CHP’s board members – some of whom represent the organizations that the panelists spoke about – would react. She prepared the board for the session by asking them to focus on active listening. After the panelists left the room, she offered time for them to reflect on the session individually and as a group.

The session, says Patricia, was “mind opening,” which seemed to be the consensus from other board members in the room. One representative was moved to offer a personal apology to the panelists for any difficulty they had endured. The rest of the meeting was spent in conversation reflecting on what had been said, identifying common barriers, and ideas for improvement.

By listening to those with lived experience and spending time in reflection, the board was able to focus on what was important, rather than taking it personally.

“As humans, we have that knee jerk reaction of ‘they’re attacking me.’ Having that time for reflection helps you realize that it’s not about you or your organization. It’s about how we can do a better job of achieving our mission because we are working together in an ecosystem.” says Patricia. “Doing systems change work means we are all accountable for how people experience the system, and we are also responsible for making their experiences better. This is the type of systems change leadership CHP is trying to collectively build in community.”

Strategic Thinking

“There’s no one, quick, or easy solution to a complex/chaotic problem,” says Amber. “We have to continually learn about what works, what doesn’t, and explore the why associated with those questions if we want to create long-lasting system change.”

CHP has a learning culture, and that culture extends to its board. This type of learning isn’t passive. It requires us to get curious, ask powerful questions, actively listen and engage, and use what we’ve learned to inform the work. Change is impossible without it.

For the board, each meeting is an opportunity to learn from one another and take what they’ve learned back to their own organizations. “It’s almost an efficacy thing,” says Patricia. “If you’re willing to ask questions and learn from your own experiences and the experiences of others, it’s going to make finding a solution easier and faster.”

By building and adopting these three foundational practices, CHP’s board members are embodying what it means to be a new kind of leader. Not only that, says Patricia, “when they leave the board, they’ll take these skills and pass them along to others and the ripple effect could be pretty amazing.”